Project Description

Interview with

JAKE BURNS

(STIFF LITTLE FINGERS)

still pointing the way forward

by ALEC SMART

.

Photo – Ashley Maile

.

Veteran punk rockers Stiff Little Fingers are touring Australia in 2018 to celebrate their 40th anniversary. The Belfast battlers will return to our shores in February for headline shows in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney.

Alec Smart caught up with singer-songwriter Jake Burns, the band’s heart and soul.

.

.

When asked if, aged 19, he predicted his abrasive-but-melodic punk quartet, Stiff Little Fingers, would last 40 years – or even 10 years – Burns replied,

“I wouldn’t have given us forty days, to be honest! I don’t think anybody that forms a band ever expects it to last, particularly a band that you form for love or the fun of it. I don’t remember ever thinking it might turn into a serious job.

“Even when we started to make records we thought we’d only get a year or two out of it.

“Sometimes, though, it feels like it’s passed in the blink of an eye, while at other times it certainly does feel like forty years.

“I can still remember the rehearsals in the little church hall in Belfast where we started out as clear as day. It’s kind of unreal that this has literally been my working life in a band. It’s a strange old thing to come to terms with.

“Of course, the other side of the coin is we’re all of us now completely unemployable at anything else, so you’re going to be stuck with us for at least another 10 or 15 years!

Did Burns come from a musical family?

“Not particularly,” he considered. “My mum was quite a good singer but she only sang after she’d had a couple of vodkas on a Saturday night!

“Both my parents were big music fans, particularly country music – Hank Williams and Patsy Cline were played a lot when I was a young kid growing up. But nobody played an instrument nor showed an inclination, so I was the first one that picked up a guitar.

“I think my parents were very glad when I got over my first fascination, which was, ‘I’d like to play drums!’ I can still see my mother’s face crumpling at that information!

Burns turns 60 mid-way through his Australian tour, on a night off between concert dates in Adelaide and Brisbane.

“Yes, I turn 60,” he confirms. “I think when I get home there’ll be a bus pass waiting for me!

“It’s a bizarre thought that I’ll be 60 but my entire working life has been in a rock band! I reckon after 40-odd years of doing this I’m now allowed to qualify and genuinely describe myself as a songwriter! Songwriting is what I wanted to do for a living when I was 14. But if you’d said to 14-year-old me that 60-year-old me will be discussing it with a journalist in Australia, about to go on tour again, having been a songwriter for 40 years, I think 14-year-old me would have laughed at you!”

.

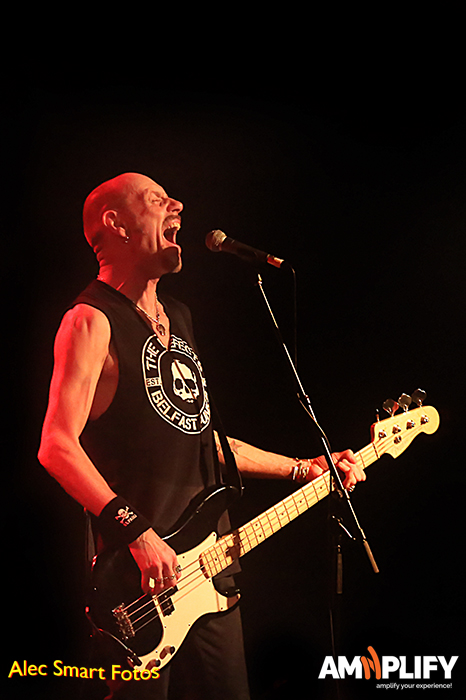

Stiff Little Fingers, The Metro, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Photo: Alec Smart, Friday 1 April 2016

.

Stiff Little Fingers – hereafter SLF – launched in 1977 during the heady days of punk rock, when Sex Pistols were creating headlines for their anarchic antics and bands like The Clash and The Ramones were gripping the music world’s attention by articulating their non-conformist fury.

Northern Ireland, SLF’s stamping ground, was experiencing a fresh surge of its centuries-old social instability with widespread sectarian conflict, aka ‘The Troubles’, polarizing the Catholic and Protestant populations.

The notorious Bloody Sunday incident happened only five years earlier, when British paratroopers shot 28 unarmed civilians, killing 14, during a peaceful protest march in Derry.

Into this caustic environment a group of fervent youths emerged armed with a more lethal weapon than guns – guitars and drums.

One night whilst performing, the teenaged SLF were introduced to a young journalist named Gordon Ogilvie, who suggested they write about the political and religious strife around them. Ogilvie himself began contributing lyrics to the band and becoming Burns’ songwriting collaborator as well as the band’s manager.

“Gordon always wanted to be a songwriter,” recalled Burns, “and through it he became the world’s most reluctant rock band manager!

“I shared an apartment with him for 10-11 years and we were quite a solid songwriting team. Apart from the fact that we sparked off one another very well, it didn’t hurt that if I suddenly had a good idea for a song my songwriting partner was literally in the next room!

“In the days before sending emails and MP3s, I could just wander in and say, ‘I’ve got this idea for a song!’ and we would disappear for a couple of hours and more often than not come back with something that we ended up using.”

SLF fused personal and political issues, incorporating rousing choruses over strong melodic hooks. Whilst weaving angst and anger into their social criticism, their lyrics often revealed a dark humour and love of wordplay.

For example, in the song Barbed Wire Love, which drew inspiration from the coils of barbed wire separating Belfast’s warring religious factions, the lyrics revealed they were more pun rockers than punk rockers.

‘It was love at bomb site’ replaced the traditional ‘love at first sight’, and, ‘You set my arm alight’, was a witty pun on ‘Armalite’, an American-made rifle for which the Provisional Irish Republican Army was renowned due to their black market-sourced quantities of the AR180 model.

.

.

However, SLF’s irony sometimes confused their listeners with songs such as Fly The Flag, which exalted people to ‘Gimme a country that’s red white and blue, Gimme the British way honest and true, Cos, I’m all right, I’m all right Union Jack, fly the flag.’

Many Loyalists supporting the British occupation of Northern Ireland and opposed to concessions given to the Catholic/Nationalistic population, interpreted this as an endorsement of continuing British rule. Yet the ironic line, ‘Free to do and free to be free to screw you before you screw me’ apparently eluded them.

Similarly, SLF’s anti-racist song White Noise was popular among Nazi skinheads who misinterpreted the delicious irony in lines like ‘Rastus is a nigger, thug, mugger, junkie,’ and, ‘Irish Paddy is a moron, spud-thick Mick, Breeds like a rabbit, thinks with his prick, Anything floors him if he can’ fight or drink it,’ and took it as literal.

During one of my many trips to Northern Ireland during the 1990s, I came across a group of punks known as the WarZone Gig Collective who ran a music venue and café in Belfast city centre called Giros. There they hosted punk rock shows that were free from the sectarian strife dividing the wider Northern Irish community and were inspired by anarchist punk ideals of cooperative management.

Belfast community photographer Sean McKernan photographed some of them on a protest march carrying a large banner painted with the words ‘Alternative Ulster’, inspired by the SLF song Alternative Ulster.

And Warzone set about creating just that, an alternative to the internecine strife plaguing Ireland’s north, refusing to submit to the vicious intimidation inflicted by paramilitary organisations waging their bloody wars of attrition.

.

Stiff Little Fingers, The Metro, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Photo: Alec Smart, Friday 1 April 2016

.

I asked Burns if he was familiar with the WarZone crew or ever played at Giros.

“No, we only played at the Royal Ulster Hall or Queens University. However, from day one, we always tried to play venues that were right in the city centre, rather than in one area or the other. If you’ve been to Belfast you know that politically and religiously it’s kind of like a patchwork quilt; you can walk from a Loyalist zone to a Nationalist one in a matter of three or four blocks.

“We always tried to be right in the city centre so people could come from either community. Nobody among us cared about those political and religious divides. I don’t remember there being any factions at any of our shows, right from day one. So, apart from the fact that we were singing about what was happening around us, nobody took us as promoting any party-political line, neither among the audience or the band.”

SLF released three scorching records during their first incarnation from 1977-83, Inflammable Material, which reached number 14 on the UK album charts and inspired their move to London, Nobody’s Heroes and Go For It, the latter introducing darker subjects such as domestic abuse and football hooliganism.

A more melodic album, Now Then, which departed significantly from the fast-and-hard format of its predecessors, followed these. Now Then was among the first punk records released by all-male bands to feature songs that discussed issues concerning women.

Unfortunately, the band then split acrimoniously, largely due to low album sales and audience attendance, and went on hiatus for five years while the members pursued solo projects.

.

.

Since their reformation, do SLF still play material from Now Then?

“Occasionally we do,” Burns replied. “From our point of view, it’s one of those records that didn’t really stand the test of time. I would need to go back and listen to it.

“The problem with being part of the creation of anything like that is you remember the growing pains and the birth pains of it. At the time we were not a particularly happy ship. There were four band members pulling in four different directions. It wasn’t a particularly confortable record to make. I think now, looking back on it, I’ve tended to re-praise is as “when it’s good, it’s very, very good, but where it’s bad I really can’t stand it.”

“Not long after we released it we decided to call it a day for awhile, so the painful memories of that override the fond memories I have of other records we’ve made.”

In 1987 the band reformed for a short reunion tour, and after attracting swathes of loyal fans, decided to make the reunion permanent.

Although bassist Ali McMordie departed soon afterwards, feeling he could not commit to full-time touring, the former bassist from The Jam, Bruce Foxton, replaced him. Foxton remained with SLF for 15 years. McMordie is now back in the band again.

The band released Flags & Emblems, a tour-de-force, which immediately got them into trouble when the single Beirut Moon was banned from airplay after it criticized the UK Government for not acting to free British journalist John McCarthy. McCarthy was held hostage in Lebanon for five years by the Hezbollah organization at the behest of the Iranian Government.

SLF released four more albums between 1993 and 2003, Get A Life, Tinderbox, Hope Street and Guitar And Drum, all continuing their commitment to tackling difficult social issues in songs featuring strong melodies with catchy choruses.

In 2007 SLF sought crowd funding for an album of new songs, resulting in No Going Back, which covered topics like the Iraq War and the world banking crisis.

The title song was a poignant anthem that dealt with Burns’ depression after his marriage failed, before he remarried and moved to Chicago, USA.

.

Stiff Little Fingers, The Metro, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Photo: Alec Smart, Friday 1 April 2016

.

Crowd funding, although common now, was an unusual method then to source funds for a recording project.

“Crowd funding works very well for bands like us that have been around awhile and have an established audience,” Burns explained. “I really wouldn’t know if it would work for a band starting out.

“When it was first suggested to us, we were a bit nervous about it, as it was our management’s idea. They said at first, ‘We can go back to EMI and we’re fairly sure they’ll give you some sort of a record deal,’ yet when we stopped and thought about it, the only real reason anybody needed a record deal was to get their record in the shops.

“However, since the rise of the Internet and the all-mighty Amazon website, record stores have been pretty much driven out of business. Apart from specialist shops and second hand stores, records are very hard to find these days.

“So although the traditional route wasn’t necessarily closed to us, there’s nothing to say that EMI would have been interested. It had been 11 years since we delivered our last record – most of the people we knew at the label were probably retired!

“The big trepidation with crowd funding is that you’re going directly to your audience and basically saying, “We’re making a new album and we kind of want you to buy it before you’ve heard it!” Which is effectively what all crowd sourcing really is – pre-ordering before it’s actually made. They’ve got to have a certain amount of faith in you.

“If you go to your own audience and say, ‘We’d like to make another record, would you like to buy it?’ and they say, ‘You know what, we’re really not that interested!’ then you’re kind of screwed! Because you can’t go to somebody else’s audience and ask them! It was a huge leap of faith on behalf of all, but crowd funding came through for us incredibly strongly. Although we actually stopped the campaign after it ran for three or four months, we actually hit the target within 12 hours! So, the investors obviously really wanted us to make another record! Which was fantastic!

“We’ve since used the crowd-sourcing thing again to record a live album and live DVD.”

.

.

Is Burns still writing songs and if so, is there another album in the works?

“We’ve already got some new songs written so I’m hoping by the time we get to Australia we get a chance to get one or two of them rehearsed up so we can start playing them for you.

“I know this is our 40th anniversary tour and it’s very much a celebration of the band’s past, but I don’t want it to make it a complete nostalgia-fest. We play stuff right up to an including the most recent album, No Going Back.

So, Australia gets the 40th anniversary celebration but with one eye on the future.”

As a soccer fan – he supports Newcastle United in the UK Premiership League (“They’re not going terribly well this year!”) – our national game has failed to impress him.

“What little I’ve seen of Australian Rules football it’s always made me chuckle that it’s called Australian ‘rules’, because the only rules seem to be you’re not allowed to knife or shoot anybody! Beyond that I don’t see any rules! It’s not a game for wimps, that’s for sure!

“I’m looking forward to playing in Australia. It’ll be your summer when I get there, but it will be the teeth of winter here. Even if we didn’t enjoy coming to play, just the weather alone would make me happy.”

.

.

Stiff Little Fingers

40th anniversary Australian tour 2018

Monday 19 February

Perth The Rosemount

Tuesday 20 February

Adelaide The Gov

Thursday 22 February

Brisbane The Triffid

Friday 23 February

Sydney Metro Theatre

Saturday 24 February

Melbourne Croxton Bandroom

Tickets

.

.