Project Description

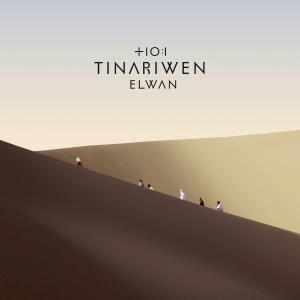

Tinariwen – Elwan (Album Review)

Imagine, if you will, that you’re in sub-Saharan Africa, sheltering from an advancing sandstorm in a large marquee, ensconced amidst the competing scents of fresh brewed coffee and musky goats.

Outside, the nomadic herders of camel, goats and zebu cattle securely corral their stock in pens as caravan trains of spice traders hastily retreat from their sunset prayers on the dunes into the animal hide pavilion for sanctuary.

The sun sinks and a chill night air supervenes the scorching heat of the day, while the fenced-in animals shut their eyes to the wind-blown grits as the storm of whirling granules blanket the spice merchants’ fastened wagons. On entering the marquee, the traders and herders gift alms to their hosts before settling down for the evening, shaking off sand and sipping strong coffee or ladles full of eghajira – a thick beverage consisting of diluted goats’ cheese and millet sweetened with ground dates.

In one corner, a group of musicians begin strumming a hypnotic drone on tambours (long-necked fretted stringed instruments) and ouds (Arabic lutes).

Then a woman supplements the strumming with a melancholic strain from her anzad (a bowed, single-stringed violin).

The takamba percussionists keep time, clattering their drums of goatskin stretched wooden gourds with sticks in spirited tattoos, some shaking containers full of beans in rhythm, and soon groups of men and women dance agabas.

This arcadian scene could have been drawn from any time over the last few centuries, in desert camps sprinkled across the Tuareg-dominated North African region, as traders trekked back and forth, bartering and biding with successive clients.

In recent years, however, despite the deliberate diversion of the old spice merchants’ cross-desert routes (imposed by successive Colonial masters), the desert dwellers would still congregate in canopies to enjoy communal meals and sanctuary from sandstorms, although the timeless tent music would be supplemented with modern six-stringed instruments – guitars.

Sadly, warring factions and oppressive regimes have led to a breakdown of the Tuareg’s traditional lifestyles and the forced dispersal of communities. In response, the sustaining Saharan symphony has evolved into the ishumar – rebel music of people challenging these injustices.

Tinariwen, a changing line-up of artists united by their love of traditional music and desires to reunite a fractured community, perhaps best personifies this melodic litany of liberation.

Formed in the 1980s by a collection of freedom fighters, several of whom had experienced unspeakable brutality by oppressive rulers during Tuareg rebellions, the group coalesced around Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, who was then performing in a popular Algerian party band with two of his brothers. The rebels soon began playing music together, recording and dispersing it on cassettes.

The name Tinariwen, meaning ‘People of the Desert’ in their Tamashek language, was given them as their reputation grew, and they embraced it forthwith.

Ag Alhabib himself grew up in refugee camps in Algeria after his father was executed during a 1963 uprising in Mali. He set his new band in motion adopting the ancient, hypnotic assouf musical style of the region, performed with modern electric guitars and sung in the common dialect of the Tuareg – Tamashek.

Among the powerless and displaced peoples spanning the border areas of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Algeria and Libya, this musical movement has spread considerably over the past 30 years. Fusing traditional North-West African rhythms played on tindé drums – made from stretching a goatskin across an open vessel such as a gourd – and combining contemporary instruments with the earlier-mentioned anzads and tambours, the ishumar lyrics urge social and political reform, whilst expressing melancholy for a lost way of life.

Ag Alhabib, who made his first guitar from a wooden pole attached to a tin can, with a steel string salvaged from a bicycle brake cable, was inspired by radical chaabi protest songs originating in Morocco, Algerian rai (popular music that originated in the multicultural port city of Oran in the 1920s), and Western rock ‘n’ roll.

It wasn’t until 2001 that Tinariwen gained a following outside of the Sahara region – they hail predominantly from Adrar des Ifoghas, a mountain range that straddles the border between north-eastern Mali and southern Algeria – with the release of their debut album The Radio Tisdas Sessions, which garnered multiple awards and gained international distribution.

Now, after 15 years together with line-ups shifting like grains of sand, criss-crossing the globe and playing hundreds of international concerts, including large alternative festivals like Glastonbury and Womad, Tinariwen release their seventh album, Elwan, meaning ‘Elephants’ in Tamashek.

Recorded at the M’Hamid El Ghizlane oasis in southern Morocco over three weeks in March 2016, as well material recorded earlier in October 2014 as the desert location of Rancho de la Luna in the Joshua Tree National Park in California, it features guest appearances by Matt Sweeney (Johnny Cash guitarist), Mark Lanegan (Queens of the Stone Age singer), Kurt Vile (The War On Drugs singer), and a Moroccan Ganga outfit comprised of Berber Gnawa trance musicians.

The album continues the band’s distinctive, hypnotic, electric guitar-driven sound over simple beats, not unlike Delta Blues music, which contemporary music historians now believe evolved from northern Africans brought to the Americas in chains via the odious slave trade.

Ag Alhabib is still a creative force in Tinariwen, contributing several songs to Elwan, such as the first single Ténéré Tàqqàl (What’s Become of the Desert?), Imidiwan n-akal-in (Friends from My Country), and Hayati (My Life).

Ténéré Tàqqàl is the first single from the album, and the accompanying animated video clip, which features, among other images, a camel trekking through the desert with guitar amplifiers strapped to its humps, was directed by Axel Digoix, a French animator-director, who worked on children’s films Despicable Me 2 and The Little Prince.

Acoustic guitarist Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni – who, like Ibrahim Ag Alhabib and Alhassane Ag Touhami, is one of the original three older members that participated in the Tuareg uprisings of the 1990s – contributes early opener Sàstanàqqàm (I Question You), one of the up-tempo numbers on the album.

However, most of the material, like the song titles, is of a slower, more contemplative nature, such as Alhassane Ag Touhami’s Ittus (Our Goal), with a leisurely riff the Rolling Stones would kill for.

Younger, more recent members of Tinariwen also contribute songs to Elwan, providing an interesting dynamism and counterbalance between the differing ages of the band. Although they didn’t experience the military conflicts that united the founder members, they have contributed significantly to the band’s overall evolution and carry it forward to a promising future.

This album slowly but surely grows on you, like sand that inevitably seeps into the crevices of your clothes and body when you trek across dunes.

Connect with Tinariwen

Reviewer Details

- Alec Smart